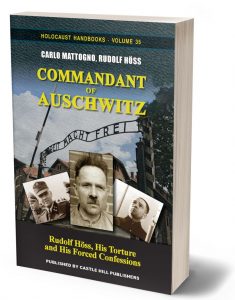

Commandant of Auschwitz: Rudolf Höss, His Torture and His Forced Confessions

by Carlo Mattogno and Rudolf Höss, English translation by Germar Rudolf. Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield, U.K., 2017, trade paperback, 402 pages.

How the Standard Holocaust Narrative Got off the Ground

By Ezra McVie

Hellishly flaming crematoria. Lines of doomed Jews trudging through the snow from cattle cars. Heartless selektions. Gas chambers! It’s all part of the gruesome furniture with which the minds of going on three generations of Westerners have been filled since the swastika flag finally came down for the last time. The insanely cruel and destructive assault upon Jewry by every non-Jew in Germany is indelibly branded upon the knowledge of every Westerner—including Germans—from childhood.

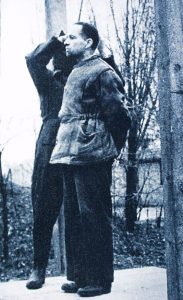

Like success itself, the wildly successful story of the Six Million has many authors,i whose ranks at this late remove still show no signs of slowing in their phenomenal growth. But pride of place in the composition and certification of the Greatest Crime in History may belong to the unfortunate SS Lieutenant Colonel from Baden-Baden whom the British nabbed in occupied Germany almost a year after the end of the war and charged with crimes committed during his tenure as commandant of the concentration camp at Auschwitz. Over the ensuing 401 days and nights, Obersturmbannführer Höss admitted to practically all the charges and obligingly if not credibly supplied virtually the entire outline of the Holocaust Story that reigns (literally, by law) supreme everywhere in the Western world to this day. He not only authoritatively supplied the horrifying, fascinating details, he did it mostly in 1946, that is, very early in the game, and he willingly signed a total of 85 affidavits and depositions in German, English and Polish—so many in fact that voluminous quotations from these qualify him to be named as co-author of the book here reviewed. His own co-author, maestro massimo of the Holocaust Carlo Mattogno, was born six years after Höss’s death by hanging at the hands of Polish executioners in that very same Auschwitz—by then reverted to its Polish name of Oswiecim—of which he had had charge for years during World War II.

Few authors indeed in the history of the written word could be said to have as profoundly influenced the content of popular belief around the world than this devoted family man who resided with his wife and five children in a house on the very grounds of the “death camp” he is said to have commanded during the war. Just how this came to be in the years following his execution would be a fascinating chronicle whose particulars would surely rival those of the aftermath of the Crucifixion, though with execration, rather than veneration, for the martyr at the heart of the story. But that is not the book here reviewed.

The first matter addressed by this paragon of meticulous historiography is exactly what Höss said (wrote, attested to), how he said it, where and when. The full-depth approach taken here—the signature approach taken by Mattogno in whatever subject he investigates—enables the reader both to trace the unfolding of what is largely Höss’s creation and to observe the glaring inconsistencies between successive presentations of the same subject, a process the author defers to Part II, the larger part by a slight margin of this magisterial work. Doing this obviously required, along with inexhaustible patience, careful scrutiny and a steel-trap memory for thousands of details, but fluency in at least English, German and Polish. Mattogno wrote in Italian and did not rely on translators for the source languages. English-language material is quoted verbatim, while translations from source material in other languages was translated into English directly from the source language.

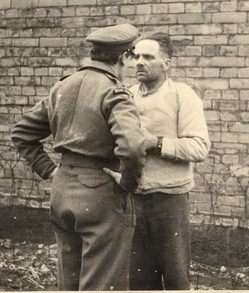

It is chiefly in Part I that the damning specifics of Höss’s odyssey through the horror-house of vengeance erected and operated by the victorious Allies in Europe is described, beginning with the terrorization of Höss’s wife and children to extract information permitting Höss’s own capture and continuing with the torture that dominated the first weeks of Höss’s time in Allied captivity. The lessons taught Höss in the benefits of cooperation with his captors are vividly portrayed in the descriptions of his handling. By the time in late 1946 when Höss was transferred to (Communist) Polish authorities, Höss had apparently mastered the life-or-death art of eliciting less-cruel, if not actually gentle, treatment from those who obviously wanted crackling good testimony from their prize captive. If only in behalf of his still-threatened family, Höss seems to have developed a large appetite for decent treatment; that in satisfying it, he condemned present and future generations of his countrymen to inextinguishable guilt and calumny seems not to have occurred to him, and indeed it would seem that such an outlandish eventuality would not have occurred to any reasonable person, even one not subject to the irresistible incentives that Defendant Höss was subject to.

The scholarly “heavy lifting” is undertaken in Part II, where the content of Höss’s testimony is analyzed both in relation to the context of events surrounding the testimony and to other testimony given by Höss on related matters—the fitting together of the pieces, to use the analogy of a puzzle or other such integrated whole. It is in this process that the image of a “motivated witness” becomes apparent, and the artifacts of fictional creativity emerge. Not until the last section (Conclusions) does Mattogno voice his interpretation that the “star witness” had indeed become starstruck in his role as the center of attention. Mattogno here implicitly neglects the fact that Höss remained as much concerned as ever not only for sparing himself any reprise of the torture to which he had been prolongedly subjected the previous year, but also for the continued safety of his wife and five children. Mattogno further ignores the Grand Prize to be at least theoretically hoped for by anyone in Höss’s predicament: clemency, or even mere delay in the imposition of the ultimate punishment.

In a final letter to his wife, reproduced in this book, Höss contritely tells her not only that he expects to be executed, but that he deserves to be executed. He expressed such thoughts on other occasions also recorded and cited in the book. He presumably did expect to be executed. But his saying so did not in any way increase the likelihood that he would be executed. To the contrary, if they had any effect at all on the likelihoods in play at the time, they would have militated against finally executing him. Ruling such strategies out of the condemned man’s mind would contradict Samuel Johnson’s famous quip, “Depend upon it, Sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.”

Endnote – Aside from outright frauds such as Binjamin Wilkomirski, the opportunists riding this “juggernaut of conscience” include Rainer Höss, grandson of the commandant, who claims that, if magically he could somehow meet his grandfather, he would kill him.

Telling Stories to Stay Alive: Rudolf Höss vs. Scheherazade

by Jett Rucker

After his capture on March 11, 1946 by British occupation troops, Rudolf Höss stayed alive for 401 days and nights, largely on the strength of the (in)credible stories he supplied concerning genocide conducted at the Auschwitz concentration camp during his tours as commandant of the camp. History contains many precedents for every element of Höss’s dolorous fate from the time of his capture. For example, in 2010, I reported remarkable similarities between Höss’s case and that of Henry Wirz, former commandant of the Confederate POW camp at Andersonville Station, Georgia, whose execution in 1865 by the US Army was the only execution of a war criminal to follow the US War between the States.

The framing story of A Thousand and One Arabian Nights itself may or may not be truly historical, but the story itself, even many of the stories within the story, have been so celebrated, so studied, translated, published, perhaps even in some cases believed, that the entire subject has very truly attained historical stature quite equal to many accounts of actual historical events and exceeding that of many, many more. Briefly, of course, there was in antiquity a king of Persia whose wife had been unfaithful to him and after he had her executed, he remarried and had his new bride executed on the day after their wedding night so as to eliminate the possibility of her being unfaithful to him. The king repeated this gruesome practice many times, never allowing his successive wives to survive for more than 24 hours after their weddings, until Scheherazade submitted herself as a bride with a secret plan to stop the carnage of innocent women.

The king duly married her, with his plan to continue his well-known practice very much in mind. But Scheherazade told her murderous husband the beginning of a story on their wedding night that so fascinated the king that he allowed her to survive until the next night so that he could hear the end of the story. It is not stated whether the king, or anyone else, actually believed the story(ies), which include such chestnuts as “Aladdin and the Magic Lamp,” “The Flying Carpet” and other charming fantasies. Scheherazade, who has gone down in (cultural) history as the consummate storyteller, finished her first story on that second night, but before turning out the lamps, she started a second story, which again captivated the king. Thus our raconteuse continued through the succeeding thousand nights, the while bearing her auditor three sons, after which the king finally abandoned his lethal plans and allowed the mother of his sons to remain alive as his queen for the rest of her natural life.

Although Rudolf Höss’s real-life (and -death) story of 1946-47 was true, the stories he told were much more like Scheherazade’s—that is, contrived so as to prolong his life. How could they not have been? At first, it is incontrovertibly known, he was tortured, and he made up stories such as the ones his torturers wished to hear so as to stop the insufferable pain he was subjected to. Then, besides the relief from the pain, his tormentors improved the circumstances of his day-to-day (the days as captive of your malefactors can be so long). Höss began, as only an idiot could fail to do, to see the way to a bearable future, however short or long it might ensue to being: tell stories—wondrous stories, impossible stories, anything to delight and fulfill the vengeful men who controlled the air you breathed, the food you ate, the cold you suffered, the light you saw. One wonders whether the precedent of Scheherazade, surely known to Höss, might have occurred to him. Either way, the path to survival, at least to tomorrow, lay down the path of incredible, horrific stories and signing the affidavits that made them documented truth, at least for the gullible, the vindictive, and those who, ultimately, had further uses for the “information,” including those who would found a new state upon it—a state today secretly numbered among those capable of raining thermonuclear destruction upon the innocent billions who live within a certain distance from the seas traversed by their submarines.

Höss had, and knew he had, far more at stake than his own flayed and bleeding skin. His arrest itself had been enabled by the capture and incarceration of his wife and five children; these remained pawns in the control of the occupying victors to do with as might best serve to elicit the desired testimony from the trembling, fear- and pain-wracked shell of a man who knew not what awaited him or his beloved family by the next dawn. That he retained the use of his formidable powers of imagination and creativity is at today’s remove an object of deserved wonderment. And he rewarded his “king” bounteously, with lurid and detailed accounts of the slaughter of millions of his hapless charges in the hell-pit of Auschwitz that he had erected and operated with hideous efficiency at the behest of Heinrich Himmler, the Reichsführer-SS himself. Scheherazade has been toppled from her perch enjoyed until then as the world’s most-creative, if not most-desperate spinner of tall tales to preserve her very life.

But Scheherazade’s tales inhabit the domain of fairy tales—no one believes in flying carpets, nor are there any laws providing prison terms for anyone announcing that they decline to believe in such things.

Rudolf Höss’s desperate flights of fancy, however, inhabit a very different domain. Upon the strength, largely, of the sworn testimony of Obersturmführer Höss, a legend has arisen to challenge such as the Immaculate Conception of Christ, the Parting of the Red Sea, even the bearing of the entire earth upon the mighty shoulders of Atlas. And this body of legend has teeth: since 1952, Germany has paid over $89 billion to victims of the Holocaust. Israel continually invokes this Holocaust, attested to by Rudolf Höss and many others under similar duress and, like Höss, subsequently executed for their troubles, in expiation of the atrocities Israel visits upon the luckless inhabitants of Palestine in the Jewish state’s relentless drive to conquer Lebensraum in the Holy Land for the Jews of today and tomorrow.

The fruits of Rudolf Höss’s last 401 nights are fully detailed in Carlo Mattogno’s 2017 Commandant of Auschwitz—Rudolf Höss, His Torture and His Forced Confessions, though Mattogno concludes that Höss, rotting in a prison cell and in fear for his wife and five children, is more motivated by gratification in being the center of much attention than by anything that might be called a Scheherazade Syndrome. Perhaps the two aren’t entirely different in the first place. But I think the Scheherazade Syndrome might, for such situations, take its place alongside, for example, the Stockholm Syndrome.

Ultimately, as with so many things about that so-called Holocaust with all its testimonies and sworn affidavits, we’ll never know. Rudolf Höss was hanged at Auschwitz on April 16, 1947. We wouldn’t have known even if he hadn’t been hanged. The Truth is ever-elusive.