“by constantly using the same three words, & then inserting a noun, publishers and writers are building a genre that sells well”

Jan27 Committee

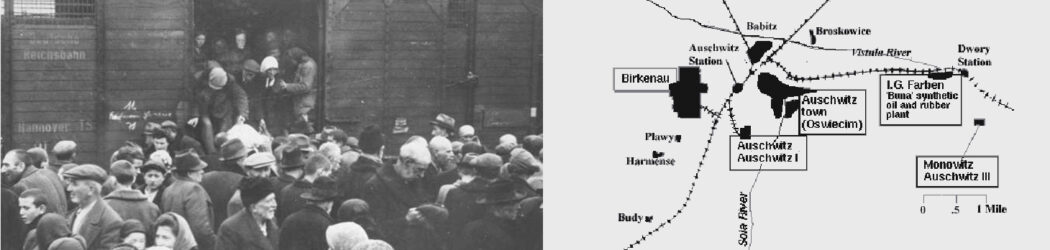

The following is taken from an article by Patrick Freyne that appeared in The Irish Times on January 11, 2020, titled “Can a work of fiction about the Holocaust be inaccurate?” Duh. The question should certainly be turned to … can it be accurate?

I have read and reviewed many holocaust novels and so-called memoirs and not found a single one that could be used for historical purposes. Some are marked as fiction, while others are not. But readers generally pay little attention to that anyway and want to believe they’re reading about real events. Therein lies these novels’ danger.

Just the other day, I watched a video from a trailer of “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas” (I have not seen the film) and could hardly believe how bad it was—in the sense of unreal, corny and overdramatized. I couldn’t continue watching it, not because it was too emotionally wrenching for me but because the characters and scenes were so unconvincing. It must have been a low-budget film.

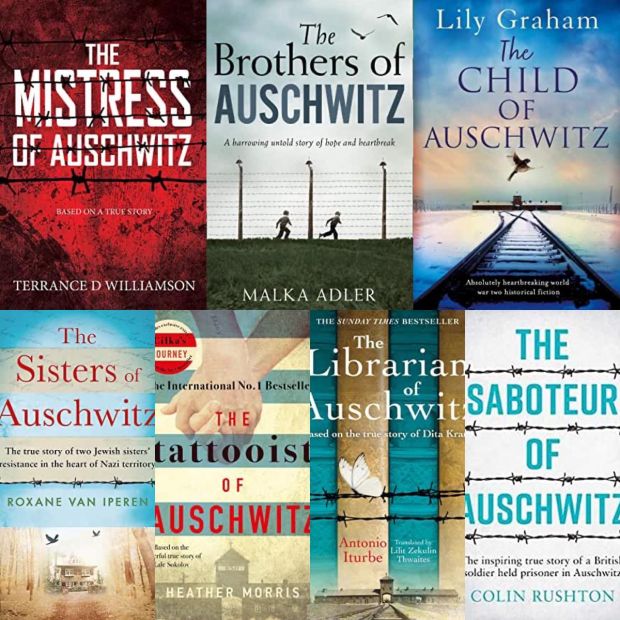

Last week, the author John Boyne [author of the best-selling Holocaust novel “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas” -ed] pointed out what he saw as a troubling trend in publishing. “I can’t help but feel that by constantly using the same three words, & then inserting a noun, publishers and writers are effectively building a genre that sells well, when in reality the subject matter, & their titles, should be treated with a little more thought & consideration,” he wrote on Twitter.

The tweet was accompanied by a picture of seven books (above): The Mistress of Auschwitz, The Brothers of Auschwitz, The Child of Auschwitz, The Sisters of Auschwitz, The Tattooist of Auschwitz, The Librarian of Auschwitz and The Saboteur of Auschwitz.

The most notable response came from the Auschwitz Memorial’s Twitter account: “We understand those concerns, and we already addressed inaccuracies in some books published. However, [John Boyne’s book] The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas should be avoided by anyone who studies or teaches about the history of the Holocaust”.

They linked to an article on an educational site, run by the Holocaust Survivors’ Friendship Association, which criticised Boyne’s story of the friendship between a Jewish child and the son of a Nazi officer, as historically inaccurate.

All holocaust novels and memoirs are historically inaccurate, so to make that point about any one or a group of them (as imaged above) is underwhelming, to say the least.

John Boyne declined to read this article, he said, because of three minor inaccuracies in the first paragraph. He was quickly excoriated by other Twitter users (he has since deleted all of his tweets), but the point on which Boyne and the Auschwitz Memorial agree – that there is a proliferation of ill-conceived Holocaust fiction – is worth exploring.

The Holocaust in literature has long been a source of tension. (Jew) Theodor Adorno said: “To write a poem after Auschwitz would be barbaric.” (Jew) Elie Wiesel wrote: “A novel about Treblinka is either not a novel or it’s not about Treblinka.”

Both comments are designed to appear profound while putting all Holocaust exaggerations and outright lies off-limits to critics.

Dr Helen Finch, an associate professor and lecturer on, among other things, “literature and the Holocaust” at the University of Leeds says that not writing about the Holocaust was never an option. “What literature can do is imagine the unimaginable and put it in a different kind of context.”

There was writing about the Holocaust from the beginning, Finch says, but it took a long time to filter into the mainstream. “The breakthroughs were made by [The Diary of] Anne Frank. I think the play particularly was huge. Then in 1978 there was a big television programme called Holocaust starring Meryl Streep. ”

Helen Finch notes that in the 1990s, the Holocaust increasingly entered popular consciousness. “It becomes part of the imaginative background against which everyone is writing now.”

According to Jew Ruth Franklin, author of A Thousand Darknesses: Lies and Truth in Holocaust Fiction, “There was a point in the late 1990s when I was researching my book… Every other day there was a new undiscovered memoir or a new novel about the Holocaust.”

Why was that? “The taboo on talking about it lessened. Also, there’s a generational issue. The children and now the grandchildren of Holocaust survivors had come of age and [were] creating their own narratives about family experience or the experience of people they knew.”

Holocaust stories are at their best when they’re second or third hand—Jews telling what they heard from other Jews or “saw with their own eyes.” Then they are free to embellish as much as they wish. For some reason these “survivors” who witnessed so much suffering are usually left untouched and live to a ripe old age.

The Auschwitz Memorial expresses only mild concern

Pawel Sawicki, press officer and educator at the Auschwitz Memorial, is worried. “There seems to be more and more books based on the story of Auschwitz that are not researched properly,” he says. “Some people say, ‘This is fiction so why do we care?’… but there are certain facts that people should respect or take into consideration.”

When asked why the Auschwitz Memorial responded to Boyne’s tweet in the way it did, they replied:

“The author of The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas made this criticism and we agreed with him as an institution because we had this concern too, but actually we [felt we] should remind people that The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas… is a completely fictional book that depicts some fictional place that is just vaguely linked with the factual story of the Holocaust and shouldn’t be used in factual education about the Holocaust.

“[We] meet visitors who come to the Auschwitz memorial and they see the villa of the commandant and say, ‘Oh this is the villa from The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas’ and then we have to explain that, no, the story in The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, from our historical perspective, couldn’t take place.”

John Boyne explains his motives

When [John Boyne] wrote The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, did he think much about the tension between telling the story of the Holocaust and exploiting it? “To be honest with you, no… It was something I’d studied very widely [his assessment, not ours -ed] but I was thinking as a writer. I was trying to tell an interesting story.

“I didn’t weigh up the moral complexity of writing a novel like this at the time. I certainly did in the years that followed, when I would travel with the book and talked to audiences and met Holocaust survivors.”

Boyne stresses that he writes fiction, not history. “The novel is subtitled ‘a fable.’ It is a work of fiction with a moral at the centre. I’m not saying that these characters existed, that this story ever happened… I have created a fictional universe populated with fictional characters…” [I cannot find those two words ‘a Fable’ on any cover used for the book. The publishers didn’t want it on the cover? Unsurprisingly, there is a study guide for 4th to 8th grade kids available too. -ed]

“My point of view is that a novel cannot have inaccuracies because it’s all made up to begin with. [This is very much the idea of Elie Wiesel about his novel Night, yet when he set his sights on winning a Nobel Prize in the mid-1980’s, he decided to insist it was a faithful record of his own internment. -ed] What it can have are anachronisms* and I don’t think there are any of those in my books.”

[*An anacronism is the representation of someone as existing or something as happening in other than chronological, proper, or historical order. – from the American Heritage Dictionary]